General Guidance

Food systems

Orientation Lens: Start with Purpose

Situating your work within systems

Systems MEL prompts practitioners to explore how their initiatives fit within the broader system and the complex pathways of change they seek to influence.

Strategic Intent, System Boundaries, and Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest help teams to navigate this exploration and identify where they can act, influence, and learn.

Before diving into tools or tracking change, systems-informed practitioners start by getting oriented within the system. This means pausing to understand where you are, who else is involved, and where you’re all trying to go. This guide introduces several foundational lenses—starting with the Strategic Intent—to help ground your work in context, purpose, and possibility.

Situating your work within systems

Systems MEL prompts practitioners to explore how their initiatives fit within the broader system and the complex pathways of change they seek to influence.

Strategic Intent, System Boundaries, and Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest help teams to navigate this exploration and identify where they can act, influence, and learn.

Before diving into tools or tracking change, systems-informed practitioners start by getting oriented within the system. This means pausing to understand where you are, who else is involved, and where you’re all trying to go. This guide introduces several foundational lenses—starting with the Strategic Intent—to help ground your work in context, purpose, and possibility.

Situating your work within systems

Systems MEL prompts practitioners to explore how their initiatives fit within the broader system and the complex pathways of change they seek to influence.

Strategic Intent, System Boundaries, and Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest help teams to navigate this exploration and identify where they can act, influence, and learn.

Before diving into tools or tracking change, systems-informed practitioners start by getting oriented within the system. This means pausing to understand where you are, who else is involved, and where you’re all trying to go. This guide introduces several foundational lenses—starting with the Strategic Intent—to help ground your work in context, purpose, and possibility.

01

The Strategic Intent

Defining a Strategic Intent

Your Strategic Intent is a shared long-term purpose that reflects the systems change you want to help bring about. It provides clarity of direction, especially when working in complex, evolving systems. It’s not a fixed destination, but a shared directional anchor—helping you stay aligned with your deeper purpose as you learn, adapt, and navigate complexity.

A strong Strategic Intent:

Points toward a future that’s transformational, not just incremental.

Creates shared understanding among stakeholders with different roles.

Helps people stay purpose-driven in the face of complexity or change.

Why a Strategic Intent Matters

In complex systems, it’s easy to get pulled into short-term issues or reactive thinking. A Strategic Intent anchors your work in a shared, transformative vision. For MEL practitioners, it acts as a compass to navigate shifting circumstances, make sense of change, and stay focused on how your initiative contributes to deeper transformation.

It’s Never Too Late to Define Your Strategic Intent

Whether you’re just beginning or already deep into implementation, it’s always worth pausing to clarify your Strategic Intent. It can renew focus, strengthen alignment, and make your MEL system more purposeful—no matter where you are in your journey.

in action:

Strategic Intent in Practice

More:

How to Define a Strategic Intent

Applying the Strategic Intent in Your MEL System

01

The Strategic Intent

Defining a Strategic Intent

Your Strategic Intent is a shared long-term purpose that reflects the systems change you want to help bring about. It provides clarity of direction, especially when working in complex, evolving systems. It’s not a fixed destination, but a shared directional anchor—helping you stay aligned with your deeper purpose as you learn, adapt, and navigate complexity.

A strong Strategic Intent:

Points toward a future that’s transformational, not just incremental.

Creates shared understanding among stakeholders with different roles.

Helps people stay purpose-driven in the face of complexity or change.

Why a Strategic Intent Matters

In complex systems, it’s easy to get pulled into short-term issues or reactive thinking. A Strategic Intent anchors your work in a shared, transformative vision. For MEL practitioners, it acts as a compass to navigate shifting circumstances, make sense of change, and stay focused on how your initiative contributes to deeper transformation.

It’s Never Too Late to Define Your Strategic Intent

Whether you’re just beginning or already deep into implementation, it’s always worth pausing to clarify your Strategic Intent. It can renew focus, strengthen alignment, and make your MEL system more purposeful—no matter where you are in your journey.

in action:

Strategic Intent in Practice

More:

How to Define a Strategic Intent

Applying the Strategic Intent in Your MEL System

01

The Strategic Intent

Defining a Strategic Intent

Your Strategic Intent is a shared long-term purpose that reflects the systems change you want to help bring about. It provides clarity of direction, especially when working in complex, evolving systems. It’s not a fixed destination, but a shared directional anchor—helping you stay aligned with your deeper purpose as you learn, adapt, and navigate complexity.

A strong Strategic Intent:

Points toward a future that’s transformational, not just incremental.

Creates shared understanding among stakeholders with different roles.

Helps people stay purpose-driven in the face of complexity or change.

Why a Strategic Intent Matters

In complex systems, it’s easy to get pulled into short-term issues or reactive thinking. A Strategic Intent anchors your work in a shared, transformative vision. For MEL practitioners, it acts as a compass to navigate shifting circumstances, make sense of change, and stay focused on how your initiative contributes to deeper transformation.

It’s Never Too Late to Define Your Strategic Intent

Whether you’re just beginning or already deep into implementation, it’s always worth pausing to clarify your Strategic Intent. It can renew focus, strengthen alignment, and make your MEL system more purposeful—no matter where you are in your journey.

in action:

Strategic Intent in Practice

More:

How to Define a Strategic Intent

Applying the Strategic Intent in Your MEL System

02

System Boundaries

Defining System Boundaries

Boundaries help define what’s in your focus—and what’s not. They clarify where to concentrate your efforts, what to track, and where you hope to make change.

Your system might cover a single sector, like food production, or something broader, like a regional food system. It depends on your goals and context.

Be realistic about what you can engage with. You can’t shift everything at once. Boundaries keep your work focused while staying connected to the bigger picture.

There are two levels to consider:

The broader system

The wider context of interrelated actors, dynamics, and institutions (e.g., the global palm oil supply chain).

The core boundary

The specific part of that broader system your initiative is actively engaging with. This includes the actors, relationships, and dynamics you're working to influence.

Setting boundaries helps you:

Clarify the scope of your MEL and intervention.

Prioritize what matters most for learning and decision-making.

Stay realistic about what your team can engage with.

Reflect on whose perspectives and priorities shape the boundaries.

Why System Boundaries Matter

Without clear boundaries, complexity becomes overwhelming. Boundary setting helps you focus your MEL on what matters most—where you’re acting, what you’re influencing, and how external dynamics might shape your work. It enables you to track change meaningfully, without trying to monitor everything at once.

Note on Power and Perspective

Boundaries are shaped by values and power. They reflect who gets to decide what's important—and who or what might be overlooked.

Ask yourself:

Who decides what’s in and what’s out?

Whose knowledge or experience is considered relevant?

What actors or dynamics might be excluded—and what could that mean for equity, learning, or impact?

Making these questions explicit strengthens accountability and inclusion in your MEL practice.

in action:

Setting Boundaries in the Palm Oil System

More:

How to Define a System Boundary

Applying Boundaries in Systems MEL

02

System Boundaries

Defining System Boundaries

Boundaries help define what’s in your focus—and what’s not. They clarify where to concentrate your efforts, what to track, and where you hope to make change.

Your system might cover a single sector, like food production, or something broader, like a regional food system. It depends on your goals and context.

Be realistic about what you can engage with. You can’t shift everything at once. Boundaries keep your work focused while staying connected to the bigger picture.

There are two levels to consider:

The broader system

The wider context of interrelated actors, dynamics, and institutions (e.g., the global palm oil supply chain).

The core boundary

The specific part of that broader system your initiative is actively engaging with. This includes the actors, relationships, and dynamics you're working to influence.

Setting boundaries helps you:

Clarify the scope of your MEL and intervention.

Prioritize what matters most for learning and decision-making.

Stay realistic about what your team can engage with.

Reflect on whose perspectives and priorities shape the boundaries.

Why System Boundaries Matter

Without clear boundaries, complexity becomes overwhelming. Boundary setting helps you focus your MEL on what matters most—where you’re acting, what you’re influencing, and how external dynamics might shape your work. It enables you to track change meaningfully, without trying to monitor everything at once.

Note on Power and Perspective

Boundaries are shaped by values and power. They reflect who gets to decide what's important—and who or what might be overlooked.

Ask yourself:

Who decides what’s in and what’s out?

Whose knowledge or experience is considered relevant?

What actors or dynamics might be excluded—and what could that mean for equity, learning, or impact?

Making these questions explicit strengthens accountability and inclusion in your MEL practice.

in action:

Setting Boundaries in the Palm Oil System

More:

How to Define a System Boundary

Applying Boundaries in Systems MEL

02

System Boundaries

Defining System Boundaries

Boundaries help define what’s in your focus—and what’s not. They clarify where to concentrate your efforts, what to track, and where you hope to make change.

Your system might cover a single sector, like food production, or something broader, like a regional food system. It depends on your goals and context.

Be realistic about what you can engage with. You can’t shift everything at once. Boundaries keep your work focused while staying connected to the bigger picture.

There are two levels to consider:

The broader system

The wider context of interrelated actors, dynamics, and institutions (e.g., the global palm oil supply chain).

The core boundary

The specific part of that broader system your initiative is actively engaging with. This includes the actors, relationships, and dynamics you're working to influence.

Setting boundaries helps you:

Clarify the scope of your MEL and intervention.

Prioritize what matters most for learning and decision-making.

Stay realistic about what your team can engage with.

Reflect on whose perspectives and priorities shape the boundaries.

Why System Boundaries Matter

Without clear boundaries, complexity becomes overwhelming. Boundary setting helps you focus your MEL on what matters most—where you’re acting, what you’re influencing, and how external dynamics might shape your work. It enables you to track change meaningfully, without trying to monitor everything at once.

Note on Power and Perspective

Boundaries are shaped by values and power. They reflect who gets to decide what's important—and who or what might be overlooked.

Ask yourself:

Who decides what’s in and what’s out?

Whose knowledge or experience is considered relevant?

What actors or dynamics might be excluded—and what could that mean for equity, learning, or impact?

Making these questions explicit strengthens accountability and inclusion in your MEL practice.

in action:

Setting Boundaries in the Palm Oil System

More:

How to Define a System Boundary

Applying Boundaries in Systems MEL

03

Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest

Defining the Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest

In complex systems, change happens across many levels—and not all of it is within our reach. The Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest help clarify what your initiative can:

Do directly

Shape indirectly

Care about and learn from, even if it can’t change them alone

This framing helps you stay focused on what’s within your reach—while still keeping an eye on the broader system.

The Three Spheres Explained

01

Sphere of Control

What your team or partners can directly do or manage—like designing training, delivering services, or producing outputs.

02

Sphere of Influence

Where your work aims to shape the behavior, choices, or practices of others—like partner uptake of new approaches, or stakeholder engagement in a policy process. You can contribute to change here, but you can’t guarantee how others respond.

03

Sphere of Interest

The broader systemic or societal outcomes you care about—like environmental sustainability, gender equity, or national policy shifts. You have no direct control here, but you still observe and learn from these trends to inform strategy and adaptation.

Why the Spheres Matter

It helps teams avoid unrealistic expectations about what they can directly shape, while still encouraging learning about broader change. It’s not about stepping back from ambition—it’s about knowing where and how your work fits into the system.

Clarifying your spheres helps you design more realistic expectations, indicators, and learning questions.

It also helps you adapt more intentionally as your work begins to influence areas beyond your direct control.

in action:

Spheres in a Sustainable Agriculture Initiative

More:

Applying Spheres in Systems MEL

What’s the difference between boundaries and spheres?

03

Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest

Defining the Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest

In complex systems, change happens across many levels—and not all of it is within our reach. The Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest help clarify what your initiative can:

Do directly

Shape indirectly

Care about and learn from, even if it can’t change them alone

This framing helps you stay focused on what’s within your reach—while still keeping an eye on the broader system.

The Three Spheres Explained

01

Sphere of Control

What your team or partners can directly do or manage—like designing training, delivering services, or producing outputs.

02

Sphere of Influence

Where your work aims to shape the behavior, choices, or practices of others—like partner uptake of new approaches, or stakeholder engagement in a policy process. You can contribute to change here, but you can’t guarantee how others respond.

03

Sphere of Interest

The broader systemic or societal outcomes you care about—like environmental sustainability, gender equity, or national policy shifts. You have no direct control here, but you still observe and learn from these trends to inform strategy and adaptation.

Why the Spheres Matter

It helps teams avoid unrealistic expectations about what they can directly shape, while still encouraging learning about broader change. It’s not about stepping back from ambition—it’s about knowing where and how your work fits into the system.

Clarifying your spheres helps you design more realistic expectations, indicators, and learning questions.

It also helps you adapt more intentionally as your work begins to influence areas beyond your direct control.

in action:

Spheres in a Sustainable Agriculture Initiative

More:

Applying Spheres in Systems MEL

What’s the difference between boundaries and spheres?

03

Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest

Defining the Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest

In complex systems, change happens across many levels—and not all of it is within our reach. The Spheres of Control, Influence, and Interest help clarify what your initiative can:

Do directly

Shape indirectly

Care about and learn from, even if it can’t change them alone

This framing helps you stay focused on what’s within your reach—while still keeping an eye on the broader system.

The Three Spheres Explained

01

Sphere of Control

What your team or partners can directly do or manage—like designing training, delivering services, or producing outputs.

02

Sphere of Influence

Where your work aims to shape the behavior, choices, or practices of others—like partner uptake of new approaches, or stakeholder engagement in a policy process. You can contribute to change here, but you can’t guarantee how others respond.

03

Sphere of Interest

The broader systemic or societal outcomes you care about—like environmental sustainability, gender equity, or national policy shifts. You have no direct control here, but you still observe and learn from these trends to inform strategy and adaptation.

Why the Spheres Matter

It helps teams avoid unrealistic expectations about what they can directly shape, while still encouraging learning about broader change. It’s not about stepping back from ambition—it’s about knowing where and how your work fits into the system.

Clarifying your spheres helps you design more realistic expectations, indicators, and learning questions.

It also helps you adapt more intentionally as your work begins to influence areas beyond your direct control.

in action:

Spheres in a Sustainable Agriculture Initiative

More:

Applying Spheres in Systems MEL

What’s the difference between boundaries and spheres?

04

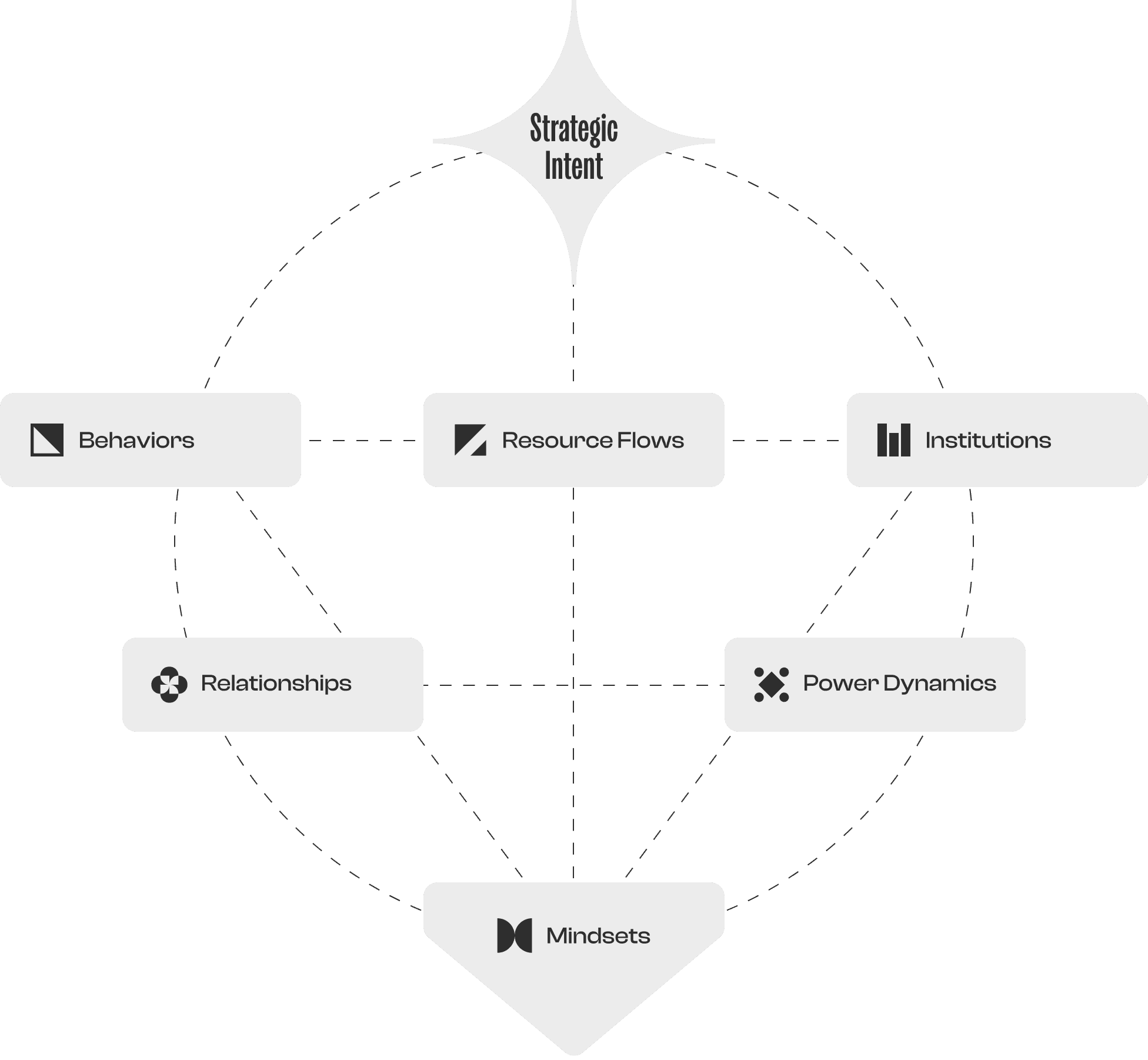

Domains of Change

Defining Domains of Change

System change doesn’t happen all at once—or in a straight line. It emerges.

The Domains of Change help us see and make sense of system change. They represent key areas—like mindsets, behaviors, relationships, institutions, resource flows, and power—where meaningful change can unfold.

These domains offer a practical way to:

Observe what’s shifting in the system.

Surface patterns, feedback loops, or leverage points.

Guide learning, reflection, and adaptation over time.

You don’t need to monitor all domains—or monitor them all at once. Start where your initiative has capacity and relevance. Even light observation or dialogue around one domain can expand your understanding of the system. Use the domains flexibly: phase them in over time, or choose one or two to explore more deeply.

More:

Understanding Domains of Change

These are the interconnected domains we seek to observe, influence, and track as the system evolves:

Mindsets (Mental Models)

Beliefs and assumptions that shape how actors see and respond to the system.

Example:

From “food security = calorie access” to “food systems = ecological and cultural wellbeing.”

Behaviors and Practices

Observable actions and routines of individuals or organizations.

Example:

Farmers shifting from chemical-intensive to agroecological practices.

Relationships and Networks

The quality and structure of interactions between actors.

Example:

Multi-stakeholder platforms that increase trust and coordination between producers, traders, and policymakers.

Institutions and Rules

Formal policies and informal norms that guide behavior.

Example:

Introduction of procurement policies favoring local producers.

Resource Flows

Movement and distribution of finance, knowledge, labor, or goods.

Example:

Access to extension services expands to marginalized communities.

Power Dynamics

How authority, influence, and voice are distributed across the system.

Example:

Women farmers gain representation in cooperative decision-making.

Use these areas to focus learning, identify leverage points, reflect on patterns, and track signs of transformation over time.

More:

“Systemic Change” vs. “System Change”

Navigating the Domains of Change: Zoom In / Zoom Out

Systems change is complex and often hard to see all at once. We propose using the Domains of Change to help you with zooming in and out of the system.

Zooming out helps you understand the big picture—how mindsets, power, and relationships interact across the system. It reveals patterns, blind spots, and leverage points for change.

Zooming in, on the other hand, lets you explore specific areas in more depth—what’s shifting, what’s stuck, and what matters most in your context.

Moving between these levels helps you stay grounded in the part of the system you are hoping to influence while staying alert to broader dynamics. You don’t need to monitor everything—start where you have insight or energy, and build from there.

You can:

Start with a light zoom-out to map the broader system landscape—then dive deeper into the Domains of Change most relevant to your work.

Alternatively, begin by zooming in on one or two key Domains central to your initiative. Then zoom out to see how other Domains influence them.

Move between zooming in and out until you’ve surfaced what you already know—and identified key learning questions to explore through your Systems MEL.

Zoom Out: See the System

Explore how these areas are interconnected:

Shifts in mindsets can unlock new practices, reconfigure relationships, and challenge entrenched institutions.

Power influences whose perspectives are heard, which resource flows are prioritized, and how rules are enforced.

This system view helps practitioners recognize patterns, feedback loops, and potential leverage points.

Zoom In: Deep Dive by Domain

Clicking into each domain reveals:

A short definition and link to systems concepts + why it matters.

Real examples.

Questions to guide observation or reflection during MEL processes.

Insights on how long change typically takes in each domain—for example, shifting mental models often takes 5–10 years.

This interaction reinforces the nonlinear, interdependent nature of systems change, while still grounding practitioners in tangible, relatable starting points.

When zooming in and out remember you don’t need to monitor all domains—or monitor them all at once. Start where your initiative has capacity and relevance. Even light observation or dialogue around one domain can expand systemic insight. Use the domains flexibly: phase them in over time, or choose one or two to explore more deeply.

Practical MEL tips for zooming in:

Start with reflection—not metrics.

Use what’s feasible and meaningful in your context.

Contribution, not attribution, is your guide.

Mindsets

Behaviors

Resource Flows

Power Dynamics

Relationships

Institutions

You don’t need to measure all domains - or quantify every shift. These suggestions offer light-touch ways to learn from shifts over time—even when attribution is unclear.

deeper learning:

Theories and Frameworks

04

Domains of Change

Defining Domains of Change

System change doesn’t happen all at once—or in a straight line. It emerges.

The Domains of Change help us see and make sense of system change. They represent key areas—like mindsets, behaviors, relationships, institutions, resource flows, and power—where meaningful change can unfold.

These domains offer a practical way to:

Observe what’s shifting in the system.

Surface patterns, feedback loops, or leverage points.

Guide learning, reflection, and adaptation over time.

You don’t need to monitor all domains—or monitor them all at once. Start where your initiative has capacity and relevance. Even light observation or dialogue around one domain can expand your understanding of the system. Use the domains flexibly: phase them in over time, or choose one or two to explore more deeply.

More:

Understanding Domains of Change

These are the interconnected domains we seek to observe, influence, and track as the system evolves:

Mindsets (Mental Models)

Beliefs and assumptions that shape how actors see and respond to the system.

Example:

From “food security = calorie access” to “food systems = ecological and cultural wellbeing.”

Behaviors and Practices

Observable actions and routines of individuals or organizations.

Example:

Farmers shifting from chemical-intensive to agroecological practices.

Relationships and Networks

The quality and structure of interactions between actors.

Example:

Multi-stakeholder platforms that increase trust and coordination between producers, traders, and policymakers.

Institutions and Rules

Formal policies and informal norms that guide behavior.

Example:

Introduction of procurement policies favoring local producers.

Resource Flows

Movement and distribution of finance, knowledge, labor, or goods.

Example:

Access to extension services expands to marginalized communities.

Power Dynamics

How authority, influence, and voice are distributed across the system.

Example:

Women farmers gain representation in cooperative decision-making.

Use these areas to focus learning, identify leverage points, reflect on patterns, and track signs of transformation over time.

More:

“Systemic Change” vs. “System Change”

Navigating the Domains of Change: Zoom In / Zoom Out

Systems change is complex and often hard to see all at once. We propose using the Domains of Change to help you with zooming in and out of the system.

Zooming out helps you understand the big picture—how mindsets, power, and relationships interact across the system. It reveals patterns, blind spots, and leverage points for change.

Zooming in, on the other hand, lets you explore specific areas in more depth—what’s shifting, what’s stuck, and what matters most in your context.

Moving between these levels helps you stay grounded in the part of the system you are hoping to influence while staying alert to broader dynamics. You don’t need to monitor everything—start where you have insight or energy, and build from there.

You can:

Start with a light zoom-out to map the broader system landscape—then dive deeper into the Domains of Change most relevant to your work.

Alternatively, begin by zooming in on one or two key Domains central to your initiative. Then zoom out to see how other Domains influence them.

Move between zooming in and out until you’ve surfaced what you already know—and identified key learning questions to explore through your Systems MEL.

Zoom Out: See the System

Explore how these areas are interconnected:

Shifts in mindsets can unlock new practices, reconfigure relationships, and challenge entrenched institutions.

Power influences whose perspectives are heard, which resource flows are prioritized, and how rules are enforced.

This system view helps practitioners recognize patterns, feedback loops, and potential leverage points.

Zoom In: Deep Dive by Domain

Clicking into each domain reveals:

A short definition and link to systems concepts + why it matters.

Real examples.

Questions to guide observation or reflection during MEL processes.

Insights on how long change typically takes in each domain—for example, shifting mental models often takes 5–10 years.

This interaction reinforces the nonlinear, interdependent nature of systems change, while still grounding practitioners in tangible, relatable starting points.

When zooming in and out remember you don’t need to monitor all domains—or monitor them all at once. Start where your initiative has capacity and relevance. Even light observation or dialogue around one domain can expand systemic insight. Use the domains flexibly: phase them in over time, or choose one or two to explore more deeply.

Practical MEL tips for zooming in:

Start with reflection—not metrics.

Use what’s feasible and meaningful in your context.

Contribution, not attribution, is your guide.

You don’t need to measure all domains - or quantify every shift. These suggestions offer light-touch ways to learn from shifts over time—even when attribution is unclear.

deeper learning:

Theories and Frameworks

Behaviors and Practices

Defining Behaviors and Practices

Behaviors and practices are the everyday actions, routines, and habits of people and organizations within a system. They show up in how work gets done—how farmers grow crops, how officials enforce policy, how decisions are made, or how people collaborate.

This domain reflects the more visible side of systems—the patterns we can observe and influence most directly.

Why Behaviors and Practices Matter

This is often where change efforts begin. New practices are tangible and easier to support than shifts in values or rules. But lasting change in behavior isn’t just about knowledge—it’s about what people see as possible, supported, and reinforced in their context.

Small shifts in routine practices—if they take root—can accumulate and signal deeper change.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Practices in the System:

What specific behaviors are shifting—or resisting change?

What patterns are emerging over time?

Are these behaviors being reinforced by relationships, rules, or incentives?

How are new ways of doing things being shared, adapted, or normalized?

Real-World Example: Sustainable Tourism

Typical Change Timelines

1–3 years for initial behavior change

3–5+ years for embedded practice

Behavior change often starts early—but it takes time to embed, scale, and sustain. Patterns become more durable when reinforced socially, institutionally, and culturally.

Tracking Behaviors in MEL

Systems Thinking in Practice – Feedback Loops

Resource Flows

Defining Resource Flows

Resource flows are about how key assets—like money, knowledge, people, and materials—move through a system. They determine who gets what, when, and how. This domain asks: Where do resources come from? Where do they go? Who is well-resourced, and who is left out?

These flows sustain the activities, relationships, and power structures in a system. Some actors are flush with resources and options, while others struggle with scarcity. Resource flows help explain why some parts of the system thrive while others stay stuck.

They include:

Financial flows (budgets, subsidies, credit)

Material flows (food, inputs, equipment)

Information and knowledge flows (extension services, market info)

Human flows (expertise, staffing, participation)

Why Resource Flows Matters

Resource flows are the system’s fuel lines. They keep certain practices going—and starve others. By shifting how resources are allocated, we can shift what the system prioritizes and sustains.

But resource flows don’t move on their own. They follow pathways shaped by policies, relationships, incentives, and power. Changing those flows often means confronting entrenched interests or redesigning institutions.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Resource Flows in the System:

What kinds of resources are flowing through the system—and who controls them?

Where are resources concentrated, and where are they lacking?

Are new types of resources or incentives emerging—and who’s benefiting?

What informal or hidden flows (e.g., favors, knowledge, social capital) are influencing outcomes?

How are resource flows shifting over time, and what patterns are becoming visible?

Real-World Example: Unlocking existing resources

Real-World Example: Changing financial flows to support information flows

Typical Change Timelines

Some resource flows can shift quickly (like small grants or pilot investments). But systemic rebalancing—especially where incentives or funding structures are entrenched—usually takes 5+ years. It requires sustained advocacy, institutional change, and feedback mechanisms to ensure resources reinforce the new direction.

Systems Thinking in Practice – Balancing Feedback Loops

Tracking Resource Flows in MEL

Institutions and Policies

Defining Institutions and Policies

This domain looks at the formal and informal arrangements that shape how systems function. These include policies, laws, and organizational procedures—as well as norms, customs, and community practices that guide behavior.

Institutions are sometimes described as the “rules of the game.” They’re not just formal rules, but the shared expectations—written and unwritten—that determine how decisions are made, who has access, and what’s seen as acceptable or possible. Policies are one way institutions show up in practice, but institutions also live in everyday routines, traditions, and social arrangements.

Note: While power dynamics are explored in a separate domain, it’s important to note that institutions often reflect and reinforce power—by determining who gets a voice, whose interests are prioritized, and how rules are enforced.

Why Institutions and Policies Matter

Institutions and policies shape the landscape in which people act. They define what’s possible, what’s prioritized, and who holds influence. Whether formal (like laws) or informal (like norms), they can open or close opportunities for people and groups—and often reflect deeper histories of power and exclusion.

That’s why institutional change is essential for systems transformation. However, policy reforms on their own rarely go far unless they’re matched by changes in enforcement, incentives, mindsets, and trust.Use what’s feasible and meaningful in your context. A new law can remove a barrier—but only if it’s implemented, accepted, and reinforced by the system around it.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Institutions and Policies in the System:

What formal policies are enabling—or blocking—change? Are informal norms reinforcing or undermining new practices?

How are new policies or institutional procedures being interpreted or enforced?

Are there gaps between policy and practice—and how are they showing up?

How have institutional arrangements or norms shifted over time?

Real-world example: Future Economy Lab: Financing Zambia’s Green Transition

Typical Change Timelines

Institutional and policy changes are often long-term efforts. While a policy might be drafted in 1–2 years, achieving effective and sustained change usually takes 5+ years. This timeline reflects the need to build legitimacy, shift power dynamics, and align enforcement, incentives, and practice.

By tracking how institutions and policies evolve—and how they influence and are influenced by other system elements—we can better understand what’s needed for sustained transformation.

Tracking Institutions and Policies in MEL

Relationships and Networks

Defining Relationships and Networks

Relationships and networks are the connections among people, organizations, and groups within a system. These connections show up in how people communicate, collaborate, and support each other. They can be formal (like partnerships) or informal (like community ties), and they shape how information flows, decisions are made, and actions are coordinated.

Why Relationships and Networks Matter

Strong, trust-based relationships enable coordination, innovation, and collective action. But when relationships are weak, siloed, or marked by distrust, change can stall—or never take off. The quality of connections matters. How people relate to and understand each other often determines whether ideas spread, groups cooperate, and change takes root.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Relationships and Networks in the System:

Which relationships are helping—or hindering—change?

Who connects different groups or sectors?

How is information flowing through the network? Are there bottlenecks or gaps?

Is there trust and mutual understanding among stakeholders?

How have relationships changed over time?

Real-World Example: Multi-Stakeholder Platforms in Agriculture

Real-World Example: From Fragmented Actors to Collaborative Networks

Typical Change Timelines

Initial connections may form in 1–2 years. But building strong, trustful networks that drive lasting change often takes 3–5+ years. These networks grow deeper and more effective over time—especially when supported and nurtured.

Tracking Relationships in MEL

Systems Thinking Concept – Nodes and Network Density

Power Dynamics

Defining Power Dynamics

Power dynamics refer to how authority, voice, and influence are distributed and exercised within a system. This includes formal power—who sets policies, holds leadership roles, or controls resources—and informal power, such as influence through social status, relationships, or control over narratives.

Power is not just held—it’s exercised and reinforced through structures, relationships, norms, and habits. It shapes who gets to speak, who decides, and what outcomes are valued.

In systems thinking, power helps explain why change takes root in some places—and stalls in others. Power dynamics show up in decision-making processes, institutional cultures, and even in what gets counted as success.

Systems are not neutral—they reflect and reinforce the interests of those with power.

Why Power Dynamics Matter

You can’t achieve systems change without shifting how power is held and shared. Power determines:

Whose knowledge is recognized

Who gets to shape the future

What gets resourced, prioritized, or blocked

If left unexamined, power dynamics can undermine collaboration, reinforce exclusion, or co-opt change efforts. Reforming a system without shifting power often reproduces the same inequities under a different name.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Power Dynamics in the System:

Who holds decision-making power in this system?

Who sets the agenda and defines success?

Whose voices are missing—or being ignored?

What informal power dynamics shape behavior or legitimacy?

Are new actors gaining influence, or are traditional gatekeepers holding on?

Real world example: Power is deeply embedded and highly contextual

Typical Change Timelines

Shifting power takes time. Even when formal structures change, deeper cultural and relational patterns often persist. It typically takes 5+ years to see sustained shifts in who holds influence and how it is exercised. Change often begins at the margins—through new coalitions, inclusive platforms, or leadership development—and ripples outward when reinforced by policy, practice, and norms.

Systems Thinking in Practice – Voice and Legitimacy

Tracking Power Dynamics in MEL

Mindsets

Defining Mindsets

Mindsets—also called mental models—are the deep beliefs, assumptions, and values that shape how people understand problems, define priorities, and decide what to do. They act like lenses through which individuals and organizations interpret the world around them.

Because they often go unspoken, mindsets can reinforce the status quo—even when policies or practices change. A system may appear to shift on the surface, but if core beliefs remain unchanged, deeper transformation can stall.

Why Mindsets Matter

These underlying beliefs influence what gets prioritized, who is trusted, and how progress is defined. Even with new policies or practices, mindsets can keep old patterns in place. But when mindsets shift, they can unlock transformational change—making other changes more meaningful and lasting.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Mindsets in the System:

What mindsets shape how this issue is currently understood?

Whose perspectives and assumptions are influencing key decisions?

What mindset shifts would support the systemic change we want to see?

Real world example: Justice

Typical Change Timelines

5–10 years

Mindset shifts usually take time. They often begin with awareness, grow through dialogue and experience, and deepen into new ways of seeing and acting.

What’s a Leverage Point?

Tracking Mindsets in MEL

The ‘’Say-Do Gap’’

Whose Mindset Shifts

Mindset shifts can happen in different stakeholder groups and across different spheres in a system:

Among interveners, as they learn and adapt their framing

Among stakeholders, such as partners or participants

Within the broader system, as dominant mental models shift over time

All are important—but it’s helpful to be clear about whose mindset is shifting, and what kind of evidence or reflection is appropriate at each level.

You don’t need to measure all domains - or quantify every shift. These suggestions offer light-touch ways to learn from shifts over time—even when attribution is unclear.

04

Domains of Change

Defining Domains of Change

System change doesn’t happen all at once—or in a straight line. It emerges.

The Domains of Change help us see and make sense of system change. They represent key areas—like mindsets, behaviors, relationships, institutions, resource flows, and power—where meaningful change can unfold.

These domains offer a practical way to:

Observe what’s shifting in the system.

Surface patterns, feedback loops, or leverage points.

Guide learning, reflection, and adaptation over time.

You don’t need to monitor all domains—or monitor them all at once. Start where your initiative has capacity and relevance. Even light observation or dialogue around one domain can expand your understanding of the system. Use the domains flexibly: phase them in over time, or choose one or two to explore more deeply.

More:

Understanding Domains of Change

These are the interconnected domains we seek to observe, influence, and track as the system evolves:

Mindsets (Mental Models)

Beliefs and assumptions that shape how actors see and respond to the system.

Example:

From “food security = calorie access” to “food systems = ecological and cultural wellbeing.”

Behaviors and Practices

Observable actions and routines of individuals or organizations.

Example:

Farmers shifting from chemical-intensive to agroecological practices.

Relationships and Networks

The quality and structure of interactions between actors.

Example:

Multi-stakeholder platforms that increase trust and coordination between producers, traders, and policymakers.

Institutions and Rules

Formal policies and informal norms that guide behavior.

Example:

Introduction of procurement policies favoring local producers.

Resource Flows

Movement and distribution of finance, knowledge, labor, or goods.

Example:

Access to extension services expands to marginalized communities.

Power Dynamics

How authority, influence, and voice are distributed across the system.

Example:

Women farmers gain representation in cooperative decision-making.

Use these areas to focus learning, identify leverage points, reflect on patterns, and track signs of transformation over time.

More:

“Systemic Change” vs. “System Change”

Navigating the Domains of Change: Zoom In / Zoom Out

Systems change is complex and often hard to see all at once. We propose using the Domains of Change to help you with zooming in and out of the system.

Zooming out helps you understand the big picture—how mindsets, power, and relationships interact across the system. It reveals patterns, blind spots, and leverage points for change.

Zooming in, on the other hand, lets you explore specific areas in more depth—what’s shifting, what’s stuck, and what matters most in your context.

Moving between these levels helps you stay grounded in the part of the system you are hoping to influence while staying alert to broader dynamics. You don’t need to monitor everything—start where you have insight or energy, and build from there.

You can:

Start with a light zoom-out to map the broader system landscape—then dive deeper into the Domains of Change most relevant to your work.

Alternatively, begin by zooming in on one or two key Domains central to your initiative. Then zoom out to see how other Domains influence them.

Move between zooming in and out until you’ve surfaced what you already know—and identified key learning questions to explore through your Systems MEL.

Zoom Out: See the System

Explore how these areas are interconnected:

Shifts in mindsets can unlock new practices, reconfigure relationships, and challenge entrenched institutions.

Power influences whose perspectives are heard, which resource flows are prioritized, and how rules are enforced.

This system view helps practitioners recognize patterns, feedback loops, and potential leverage points.

Zoom In: Deep Dive by Domain

Clicking into each domain reveals:

A short definition and link to systems concepts + why it matters.

Real examples.

Questions to guide observation or reflection during MEL processes.

Insights on how long change typically takes in each domain—for example, shifting mental models often takes 5–10 years.

This interaction reinforces the nonlinear, interdependent nature of systems change, while still grounding practitioners in tangible, relatable starting points.

When zooming in and out remember you don’t need to monitor all domains—or monitor them all at once. Start where your initiative has capacity and relevance. Even light observation or dialogue around one domain can expand systemic insight. Use the domains flexibly: phase them in over time, or choose one or two to explore more deeply.

Practical MEL tips for zooming in:

Start with reflection—not metrics.

Use what’s feasible and meaningful in your context.

Contribution, not attribution, is your guide.

Mindsets

Behaviors

Resource Flows

Power Dynamics

Relationships

Institutions

deeper learning:

Theories and Frameworks

Behaviors and Practices

Defining Behaviors and Practices

Behaviors and practices are the everyday actions, routines, and habits of people and organizations within a system. They show up in how work gets done—how farmers grow crops, how officials enforce policy, how decisions are made, or how people collaborate.

This domain reflects the more visible side of systems—the patterns we can observe and influence most directly.

Why Behaviors and Practices Matter

This is often where change efforts begin. New practices are tangible and easier to support than shifts in values or rules. But lasting change in behavior isn’t just about knowledge—it’s about what people see as possible, supported, and reinforced in their context.

Small shifts in routine practices—if they take root—can accumulate and signal deeper change.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Practices in the System:

What specific behaviors are shifting—or resisting change?

What patterns are emerging over time?

Are these behaviors being reinforced by relationships, rules, or incentives?

How are new ways of doing things being shared, adapted, or normalized?

Real-World Example: Sustainable Tourism

Typical Change Timelines

1–3 years for initial behavior change

3–5+ years for embedded practice

Behavior change often starts early—but it takes time to embed, scale, and sustain. Patterns become more durable when reinforced socially, institutionally, and culturally.

Tracking Behaviors in MEL

Systems Thinking in Practice – Feedback Loops

Resource Flows

Defining Resource Flows

Resource flows are about how key assets—like money, knowledge, people, and materials—move through a system. They determine who gets what, when, and how. This domain asks: Where do resources come from? Where do they go? Who is well-resourced, and who is left out?

These flows sustain the activities, relationships, and power structures in a system. Some actors are flush with resources and options, while others struggle with scarcity. Resource flows help explain why some parts of the system thrive while others stay stuck.

They include:

Financial flows (budgets, subsidies, credit)

Material flows (food, inputs, equipment)

Information and knowledge flows (extension services, market info)

Human flows (expertise, staffing, participation)

Why Resource Flows Matters

Resource flows are the system’s fuel lines. They keep certain practices going—and starve others. By shifting how resources are allocated, we can shift what the system prioritizes and sustains.

But resource flows don’t move on their own. They follow pathways shaped by policies, relationships, incentives, and power. Changing those flows often means confronting entrenched interests or redesigning institutions.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Resource Flows in the System:

What kinds of resources are flowing through the system—and who controls them?

Where are resources concentrated, and where are they lacking?

Are new types of resources or incentives emerging—and who’s benefiting?

What informal or hidden flows (e.g., favors, knowledge, social capital) are influencing outcomes?

How are resource flows shifting over time, and what patterns are becoming visible?

Real-World Example: Unlocking existing resources

Real-World Example: Changing financial flows to support information flows

Typical Change Timelines

Some resource flows can shift quickly (like small grants or pilot investments). But systemic rebalancing—especially where incentives or funding structures are entrenched—usually takes 5+ years. It requires sustained advocacy, institutional change, and feedback mechanisms to ensure resources reinforce the new direction.

Systems Thinking in Practice – Balancing Feedback Loops

Tracking Resource Flows in MEL

Institutions and Policies

Defining Institutions and Policies

This domain looks at the formal and informal arrangements that shape how systems function. These include policies, laws, and organizational procedures—as well as norms, customs, and community practices that guide behavior.

Institutions are sometimes described as the “rules of the game.” They’re not just formal rules, but the shared expectations—written and unwritten—that determine how decisions are made, who has access, and what’s seen as acceptable or possible. Policies are one way institutions show up in practice, but institutions also live in everyday routines, traditions, and social arrangements.

Note: While power dynamics are explored in a separate domain, it’s important to note that institutions often reflect and reinforce power—by determining who gets a voice, whose interests are prioritized, and how rules are enforced.

Why Institutions and Policies Matter

Institutions and policies shape the landscape in which people act. They define what’s possible, what’s prioritized, and who holds influence. Whether formal (like laws) or informal (like norms), they can open or close opportunities for people and groups—and often reflect deeper histories of power and exclusion.

That’s why institutional change is essential for systems transformation. However, policy reforms on their own rarely go far unless they’re matched by changes in enforcement, incentives, mindsets, and trust.Use what’s feasible and meaningful in your context. A new law can remove a barrier—but only if it’s implemented, accepted, and reinforced by the system around it.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Institutions and Policies in the System:

What formal policies are enabling—or blocking—change? Are informal norms reinforcing or undermining new practices?

How are new policies or institutional procedures being interpreted or enforced?

Are there gaps between policy and practice—and how are they showing up?

How have institutional arrangements or norms shifted over time?

Real-world example: Future Economy Lab: Financing Zambia’s Green Transition

Typical Change Timelines

Institutional and policy changes are often long-term efforts. While a policy might be drafted in 1–2 years, achieving effective and sustained change usually takes 5+ years. This timeline reflects the need to build legitimacy, shift power dynamics, and align enforcement, incentives, and practice.

By tracking how institutions and policies evolve—and how they influence and are influenced by other system elements—we can better understand what’s needed for sustained transformation.

Tracking Institutions and Policies in MEL

Relationships and Networks

Defining Relationships and Networks

Relationships and networks are the connections among people, organizations, and groups within a system. These connections show up in how people communicate, collaborate, and support each other. They can be formal (like partnerships) or informal (like community ties), and they shape how information flows, decisions are made, and actions are coordinated.

Why Relationships and Networks Matter

Strong, trust-based relationships enable coordination, innovation, and collective action. But when relationships are weak, siloed, or marked by distrust, change can stall—or never take off. The quality of connections matters. How people relate to and understand each other often determines whether ideas spread, groups cooperate, and change takes root.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Relationships and Networks in the System:

Which relationships are helping—or hindering—change?

Who connects different groups or sectors?

How is information flowing through the network? Are there bottlenecks or gaps?

Is there trust and mutual understanding among stakeholders?

How have relationships changed over time?

Real-World Example: Multi-Stakeholder Platforms in Agriculture

Real-World Example: From Fragmented Actors to Collaborative Networks

Typical Change Timelines

Initial connections may form in 1–2 years. But building strong, trustful networks that drive lasting change often takes 3–5+ years. These networks grow deeper and more effective over time—especially when supported and nurtured.

Tracking Relationships in MEL

Systems Thinking Concept – Nodes and Network Density

Power Dynamics

Defining Power Dynamics

Power dynamics refer to how authority, voice, and influence are distributed and exercised within a system. This includes formal power—who sets policies, holds leadership roles, or controls resources—and informal power, such as influence through social status, relationships, or control over narratives.

Power is not just held—it’s exercised and reinforced through structures, relationships, norms, and habits. It shapes who gets to speak, who decides, and what outcomes are valued.

In systems thinking, power helps explain why change takes root in some places—and stalls in others. Power dynamics show up in decision-making processes, institutional cultures, and even in what gets counted as success.

Systems are not neutral—they reflect and reinforce the interests of those with power.

Why Power Dynamics Matter

You can’t achieve systems change without shifting how power is held and shared. Power determines:

Whose knowledge is recognized

Who gets to shape the future

What gets resourced, prioritized, or blocked

If left unexamined, power dynamics can undermine collaboration, reinforce exclusion, or co-opt change efforts. Reforming a system without shifting power often reproduces the same inequities under a different name.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Power Dynamics in the System:

Who holds decision-making power in this system?

Who sets the agenda and defines success?

Whose voices are missing—or being ignored?

What informal power dynamics shape behavior or legitimacy?

Are new actors gaining influence, or are traditional gatekeepers holding on?

Real world example: Power is deeply embedded and highly contextual

Typical Change Timelines

Shifting power takes time. Even when formal structures change, deeper cultural and relational patterns often persist. It typically takes 5+ years to see sustained shifts in who holds influence and how it is exercised. Change often begins at the margins—through new coalitions, inclusive platforms, or leadership development—and ripples outward when reinforced by policy, practice, and norms.

Systems Thinking in Practice – Voice and Legitimacy

Tracking Power Dynamics in MEL

Mindsets

Defining Mindsets

Mindsets—also called mental models—are the deep beliefs, assumptions, and values that shape how people understand problems, define priorities, and decide what to do. They act like lenses through which individuals and organizations interpret the world around them.

Because they often go unspoken, mindsets can reinforce the status quo—even when policies or practices change. A system may appear to shift on the surface, but if core beliefs remain unchanged, deeper transformation can stall.

Why Mindsets Matter

These underlying beliefs influence what gets prioritized, who is trusted, and how progress is defined. Even with new policies or practices, mindsets can keep old patterns in place. But when mindsets shift, they can unlock transformational change—making other changes more meaningful and lasting.

Guiding Questions

These example questions offer a starting point for exploring Mindsets in the System:

What mindsets shape how this issue is currently understood?

Whose perspectives and assumptions are influencing key decisions?

What mindset shifts would support the systemic change we want to see?

Real world example: Justice

Typical Change Timelines

5–10 years

Mindset shifts usually take time. They often begin with awareness, grow through dialogue and experience, and deepen into new ways of seeing and acting.

What’s a Leverage Point?

Tracking Mindsets in MEL

The ‘’Say-Do Gap’’

Whose Mindset Shifts

Mindset shifts can happen in different stakeholder groups and across different spheres in a system:

Among interveners, as they learn and adapt their framing

Among stakeholders, such as partners or participants

Within the broader system, as dominant mental models shift over time

All are important—but it’s helpful to be clear about whose mindset is shifting, and what kind of evidence or reflection is appropriate at each level.

You don’t need to measure all domains - or quantify every shift. These suggestions offer light-touch ways to learn from shifts over time—even when attribution is unclear.

Implemented by:

United Nations

Development Programme

FUNDED BY:

MEL 360 is part of the Systems, Monitoring, Learning and Evaluation initiative (SMLE) of UNDP funded by the Gates Foundation.

CONTACT US AT:

WEBSITE DESIGNED IN 2025 BY RAFA POLONI AND BEATRIZ JANONI FOR UNDP

Implemented by:

United Nations

Development Programme

FUNDED BY:

MEL 360 is part of the Systems, Monitoring, Learning and Evaluation initiative (SMLE) of UNDP funded by the Gates Foundation.

CONTACT US AT:

WEBSITE DESIGNED IN 2025 BY RAFA POLONI AND BEATRIZ JANONI FOR UNDP

Implemented by:

United Nations

Development Programme

FUNDED BY:

MEL 360 is part of the Systems, Monitoring, Learning and Evaluation initiative (SMLE) of UNDP funded by the Gates Foundation.

CONTACT US AT:

WEBSITE DESIGNED IN 2025 BY RAFA POLONI AND BEATRIZ JANONI FOR UNDP